Kyle Myles is a photographer currently living and working in Baltimore. I got to know Kyle a few years ago through Instagram and mutual friends in the photo community, and I’m proud to count him as a friend. Long before I met him, I knew Kyle for his beautifully composed and heartfelt work, mostly focusing on personal and family documentary, as well as for his mastery of black and white - which he used almost exclusively until recently. I had the pleasure of speaking to Kyle a few weeks ago, and we talked about living with the ongoing uncertainty of coronavirus, his recent use of color, the impact of the iPhone, and hot dog days at the pool.

Sebastian: So what have you been up to with COVID-19 and quarantine?

Kyle: In a way, it's been business as usual. It hasn’t really changed much for me photographically, because a lot of work anyways is around the house or out walking around by myself, or with the family sometimes. So I’ve seen a lot of people talking about like, “How have you adjusted to photographing?” You know, the people that work in the street, candid photos of people, or portrait photographers. And for me, it hasn't really changed anything. I’ve been in the house more, so I’ve been maybe making more photos than usual just in our apartment. But, it’s kind of just… I guess the work inherently has become about it, in a way, because that's what's going on. But it's not really like, “here’s my COVID project,” or my quarantine work. It's just made during this time. And I guess it's influenced by that in some ways, but it’s still been the norm for me.

S: Yeah, that makes sense. It's interesting, because you almost don't need to be approaching it with a documentary kind of mindset for it to function that way. Since this is affecting everything so much, it's going to reflect in the work.

K: Yeah, absolutely. It just inherently becomes about it. There's definitely photos I've made with it in mind, of scenes around the neighborhood. Or that just kind of resonate things that I'm feeling about it, or that are kind of directly reflective of it in some ways.

S: Yeah, on the one hand, it's good for the work to reflect what's going on. On the other hand, even though it’s so pervasive, it still is temporary. In some ways things might change for good, but in other ways, we’ll eventually go back to some kind of new normal. So I don’t want the photos I take now to just be about COVID. The best example is if you have a photo where everyone’s wearing a mask, if it’s like a street photo or something, it ties it to this time.

K: Exactly, yeah.

S: Whereas I think your recent work that I’ve seen, if you know that it’s taken during COVID, you can read into it, but I think it still works with your other pictures. For me, I don't want my photos during this time to feel like they're limited. It’s almost the opposite of wanting to document it. I just want to continue doing what I'm doing. And you might be able to read into it, that this was during COVID, but the work is not really about it.

K: Yeah, the mask thing has been… I wouldn't call it a problem, but it's just kind of as soon as you have a photo of a person in a mask, it's a coronavirus picture, in a way. It could be beyond that, but anyone with any experience during this, somewhere down the road, is going to read it as, there’s a place marker, or a time marker – “oh, that was during that.” I'm sure there will be more of these in the future. So maybe that won’t be the case down the road.

S: And also I feel like it won't end in a very abrupt way. I think it's going to be a gradual thing, and kind of linger for a while. Even if there’s a vaccine or whatever, I just don’t think it’s going to suddenly be like, “ok, now we’re done with that!” So actually, maybe in twenty years, pictures with masks won't be that specific.

K: It’ll be like the new pictures with phones. That’ll be the time marker, in like 2032.

S: One thing I did notice in your recent work - there’s a fair amount of straight landscape more than I feel like I’ve seen in your work previously. Is that a conscious thing?

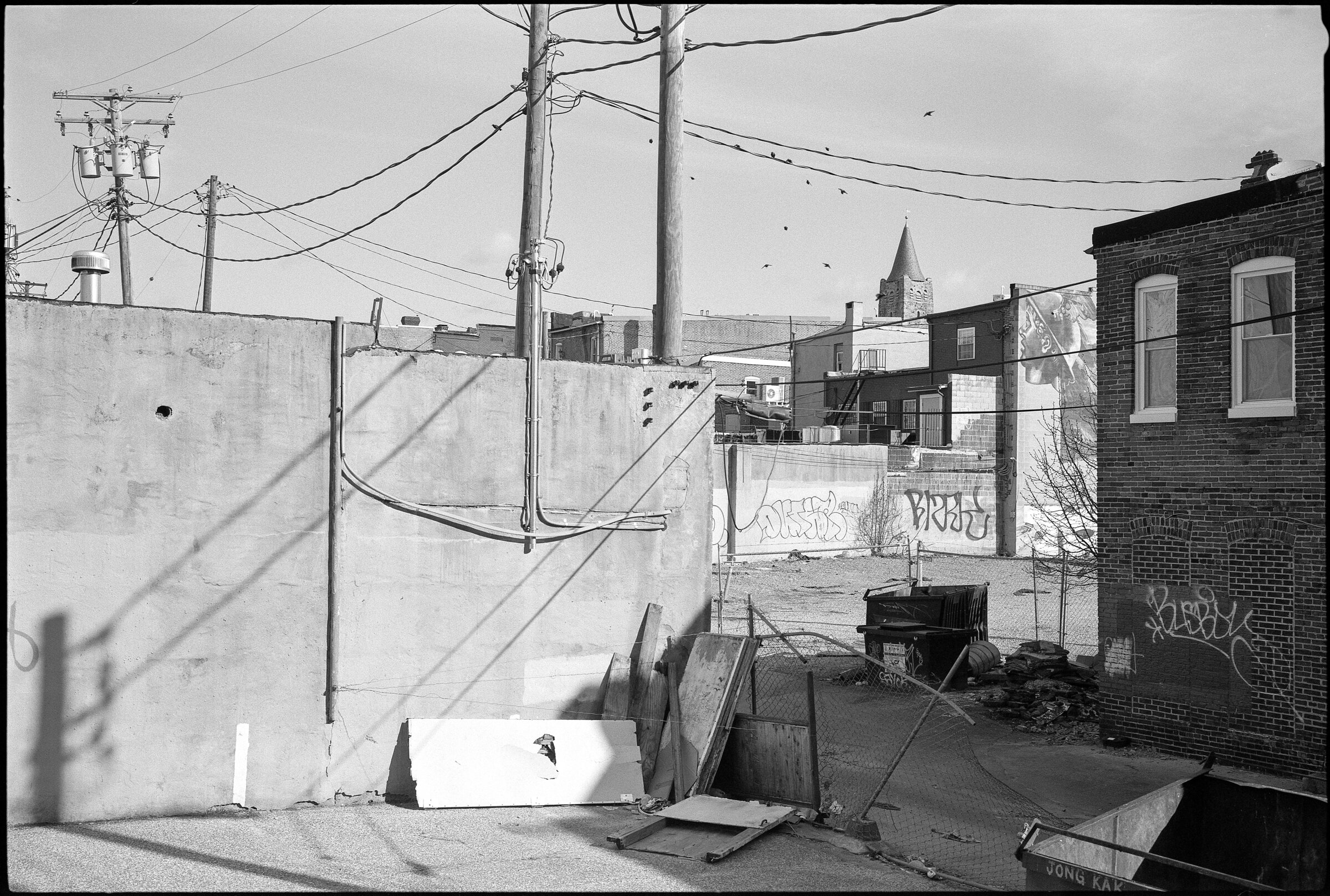

K: It wasn’t something borne out of what is going on now. That's kind of developed in the work I've been doing in the last six or seven months or so. And I’m still kind of figuring out what that work is, but it’s a lot of landscape. Maybe social landscape is the right word, but it's kind of just work about the relationship between people and the natural landscape. Or the manmade landscape, and the way people interact with it. So pretty much all of the photos, there's always some kind of human element or effect on the landscape. Some of them are photos of development, or agriculture, or construction, and some of them aren't always so clear. It could be subtle effects from people, but often it deals with it in that way, one way or another. I’m still kind of piecing together what I’m getting at with all of that. It’s still kind of early in that work.

S: Was that something that you became consciously interested in as you went out to shoot, or was it more that you started to notice it in your photos and now you’re pursuing it?

K: I don't think initially it was a conscious thing. I guess it’s work I’ve done in the past, like in the last year or two, but hadn’t really thought much of it. I took a trip to Pittsburgh in October or November and ended up doing some of that work subconsciously, and then I showed the work to a friend of mine. And he was like, “What if you continue expanding on this idea for 6 months to a year, and keep making that work?” Because a lot of these photos don't really speak to a certain geographic location. Most of them could be anywhere. You might know that it’s an east coast industrial city, like Pittsburgh, or it could be Baltimore, or it could be Virginia – it could be anywhere, relatively. It’s not about a specific place. So I’ve been trying to expand on that anywhere that I see fit, that makes sense for that type of work.

S: I get the impression, looking at your work, that you shoot continuously, and then if projects happen, it's more of a response to the work, to seeing patterns in it. But do you ever embark on something at the outset, or say “I'm going to focus on this,” or is it mainly that feedback loop of seeing the work first?

K: I guess the two zines I did last year were kind of thought out initially. The first one, Early Days, was about the first months after leaving my full-time job, kind of adjusting to that new world of mine. And that became a conscious thing. In the first week, it was like, “ok, let me give myself a month” and just photograph this change, and see what comes through in that work. And then the second one was Tori and I moving into our first apartment together, and documenting that. It was just kind of photographing every day and inhabiting a new space and what comes along with that, adjusting to a home of our own together. So both of those were borne out of time, or periods of change for me personally. Beyond that, most of the other work has just been photographing, and then somewhere along the line seeing what patterns come out of it. There’s also the summer work that I’ve shown you, which is an ongoing thing. That one kind of happened… it just kind of like became a thing on its own. I got the title for it, and that’s what made me start shooting it.

S: What’s the title?

K: So the summer work – last summer, it was the first day of summer. I was going to my mom's house, about to go on a trip with her and the rest of my family to Virginia, and I was coming into her neighborhood, and there was a sign in her neighborhood for an event at the pool that weekend, for the first weekend of summer. And it was called “Hot Dog Days at the Pool.” And I saw that, and it was like an epiphany. It was just given to me. It was like, “ok, this is it.” This has to be something, because the title was too good. And I had just bought like 50 rolls of color film, and that's all I had with me. So I shot that whole weekend thinking about that title. And so it's become a summer project of color photos, and I don't really know what the end result is going to be. But it's just my experience and interpretation of summertime. I don’t know how long it’s going to last – I know it’ll be at least this summer, as well. But that one just kind of came to me on its own. It just happened very organically. I’m not very conceptual, so that just popped up. I saw those words, and that weekend I just shot thinking about it. And I was like, let me just keep shooting all summer in color, and I think it was 80 rolls or something, and I'm still scanning that stuff now. And now here we are, and I guess there’ll be another summer of it.

S: Yeah, that’s funny how… I don’t title or caption most of my work, but there’s an interesting relationship sometimes with words and photographs, where I think a certain phrase jumps out or sticks in your head. The biggest example I can think of is that zine that I put together a few years ago with some different people's work. It was called MAN+DOG and it just… same way, it came to me and then it had to be exactly that. I knew immediately that it was going to be this army font, and what the cover was going to look like, and it just clicked. Maybe another example would be Gus Powell’s Family Car Trouble. There's just certain phrases or titles that kind of seem to jump out, and they can be really nice to tie some loose ends together, in a way. I think photographs have this way of being very abstract, and sometimes just the littlest bit of text or title can help put them together.

K: Yeah, if the title or those words come to you first, it kind of gives you a framework to work within from the beginning. There’s two different approaches, I guess. There’s also the approach of just shooting, and then piecing something together and putting a title on that work. Or, the title comes to you and then you're kind of working within whatever your interpretation of that title is. And this is my first time working in that way. I don’t know if it’s a better approach, but it's worked well for me, just thinking about that and continuing to expand on, what is the feeling that I get from those words, and what images come to mind? What works within that? And it’s not something I’m thinking of consciously while I’m shooting, but when I’m going through and editing, I’m kind of thinking, what fits the feeling that I get from that title? So it’s been a different approach.

S: And the two aren’t mutually exclusive. Because as you said, it can inform how you edit the pictures, not even necessarily what you choose to photograph in the moment.

K: For sure. And maybe there’s a mix between the two. You have an initial idea, you have this term, this phrase or this word you’re thinking of, and that’s what you have in mind when you're working. And then you come to something else, and maybe the project becomes something totally different that isn't even remotely related to where you were at beginning. So there’s a lot of different, fluid approaches. You can come at it from all sorts of angles.

S: That makes me think of something else, since you develop your own black and white at home, typically, right?

K: Yeah, always.

S: So is there a difference in that project in that with black and white, because you're doing it yourself, you can do it on a more continuous basis? Whereas that color work, because you’re relying on a lab, you might sit on larger batches of it, and you don't see it right away. Does that affect how that project is coming together for you?

K: I think with that work, there's no influence of the work that I'd already made. With black and white, typically I develop whenever I have enough rolls to fill the tank. So if I have three rolls of 120 or five rolls of 35, I develop. But that color work – it was totally uninfluenced by the work prior, from the month earlier. There were no place markers, like “okay, this is where I'm at with this project. These are the photos I have. What do I need to expand on, what pieces are missing?” It was totally just reacting every day to what was around, and not really having a benchmark of what's there. It’s been a different approach. I sat on those rolls for a while, and it was mostly a financial thing. Like, it always came down to, do I develop 20 rolls? Or do I buy another bulk roll of film so I can keep shooting? The answer is almost always to shoot more. But if I ever had a spare $20, I would get 5 rolls developed.

S: I think that’s inherent with any work that you rely on somebody else to develop. I’ve always worked that way too, in batches. I only get it developed when I have 20 or 30 rolls or something like that. And then I sit and edit it for a while, and then the cycle sort of repeats. It’s always this burst of shooting, and then a little bit of a lull. I'm kind of having that right now; I had probably 6 or 8 weeks where I was shooting all the time, and I now I have a bunch of rolls that I'm going through. And then in another few days I’ll probably start going back out again.

K: Yeah, and something I’ve thought about recently too, seeing the work that I’ve been shooting. I haven't developed the last two or three weeks, and I realized that I'm the type that needs to constantly see the work that I'm making to keep feeding off of that. I need to know that there's something there, or just seeing where I'm at with the photos. I always have ones in mind that I’ve made, but I need that cycle of shooting, developing, seeing the work, repeat, and just keep doing that. It's just kind of something that keeps me moving forward.

S: Do you see posting or sharing as part of that cycle that's important?

K: I don't think that's important to making work. I mean usually, if I have a photo that I think is interesting or maybe that I think is successful, and if it's not something in a project I'm working on, I'll share it. But I don't think it's really something that influences my daily process of making work. It's just kind of like, “I think this is interesting. Here's this. Check this out.” It’s not something that’s a motivation when I'm out making photos or looking at the work.

S: Which is interesting, because I think it can be. I definitely remember a phase, probably around 2017, when Instagram still felt sort of vibrant. And it was always this cycle of shoot, edit, post. And that feedback and interaction, I thought it was productive. And then at some point it just kind of fizzled out… at least my need for it. And then it became more like, no, it actually feels good to sit on things for a little while. And now for me it's almost gotten to a perverse level, where it’s almost painful for me to think about what to post, and I like hoarding the stuff.

K: Yeah <laughs> I mean, of course there’s that initial satisfaction when you put something out there and it's well received, people are responding to it. There’s that initial rush, and it’s like, “this is great.”

S: Which can motivate you to shoot, then, too.

K: Yeah, obviously that can kind of motivate you in a way. But I find more and more… it doesn’t really have that same effect. The further I’ve gone along, that doesn't really influence it as much as I’m sure it did in the past. I’m sure we’ve all had periods when you’ve had a successful image, or when you put it on social media and then people respond to it really well and there's all these positive reactions. And then you're like, “Okay, how do I repeat that? What was the formula there?” And I’ve realized more and more, I don't think that's always the benchmark of a successful photo… just a positive reaction.

S: I agree. I think there are a couple of different ways you can look at it. One is that way, which is probably not productive. But I think the positive spin on it is, it can make you feel good. It can make you feel that people are responding to your work, or understanding what you’re putting out there, and it just makes you want to go take more pictures. And just do your thing. The difference between those two effects is probably small, and I think one can be kind of dangerous. And the other… I’m not sure that it’s worth that, you know? But I think that there’s some element of it that can be more generally like, “Oh, I'm doing okay.” Also, if there’s someone who you respect and they like it or write a nice comment, that makes you feel like, “Okay. Good. I have something to say.” What I'm doing is worthwhile, and I want to keep doing it.

K: Yeah, absolutely. But you can always get that same thing if you share a portfolio of ongoing work with somebody that you respect, and get that same kind of feeling. Or not. Maybe it’s a negative response, and that’s fine too. I know I’m definitely the type that can overshare at times, and I think there's something to be said for… I’ve been enjoying lately just sitting on more of the work than I'm sharing, and trying to hold back the ones that I think really resonate, keeping those tucked away – so if a project does develop, I have those there.

S: Yeah, me too. Going back to the summer thing… I’m trying to figure out a way of asking about black and white versus color that’s not just…

K: That’s not, “black and white versus color?”

S: Right! So obviously you’re someone who’s committed to black and white in a serious way, it’s not just some casual thing. So I guess the best way I can think of asking it is, what does black and white mean to you?

K: It’s definitely the preferred language – if that's the right term – or format. I think I've definitely conditioned myself to see most scenes a black and white way. And not that you can't do this with color, but something like form and shape and geometry to scenes, and the way things relate to one another – for me, that's more clear and more pronounced with black and white. And I know this has been said a million times, but with color, there's just the issue of dealing with color. And I have a hard time with that. So that’s why the summer project has been a different experience for me. I think I just prefer seeing things in – and it seems I photograph in – a more monochrome kind of way, where the color isn't something that informs the image. For me that's just like an added element to deal with. And that sounds lazy, but I know it goes both ways.

S: I don’t think it’s lazy. I would say, looking at your work, I'm obviously aware that it's black and white. But… let me put it this way: to do black and white today is obviously a conscious choice, it's not the default. And I think there’s some photographers today where you look at their black and white work, whether it's digital or film, and it just looks like a filter applied on the world. The picture could have existed either way, but they’re choosing black and white for a certain aesthetic. Whereas I feel like the world in your pictures is complete, and I don't think “oh, he's making it black and white.” It just feels like that's your take on the world. I mean, I’m not asking a question… but I think there's black and white as an effect, and then there's black and white as a way of expressing…

K: As a response…

S: Exactly.

K: Yeah. I'm sure a lot of people would agree, but when you stick to one format for a long, extended period of time, after a while it doesn't really become about one or the other. I’m not thinking about black and white when I'm photographing. I know that it will be, but it’s not a conscious thought. I’m just not thinking about the color. That’s all it comes down to – that’s not a conscious thought in my head, the colors in a scene. And I have a lot of respect for color photographers who can use color well, and I think that has to be a conscious – maybe it doesn't have to be a conscious decision, but I think for a lot of people it is – but for me that’s something that can make or break an image, and that's just not something that's in my mind when I'm working.

S: I think it can be conscious and unconscious at the same time. Even like Ian Johnson, who I just spoke to, that's a very conscious use of color.

K: Yeah, the pictures are about color, in a way.

S: Whereas someone like me, I feel very committed to shooting in color, and yet I don't really think about it at all when I'm making the pictures. In the same way as the black and white for you, it's just become incorporated. And I probably have some intuitive sense of how it's going to work, but I don't really seek colors. I'm not trying to create something specific with the color. It definitely affects the way that I edit – of course there’s some things that you just look at and you’re like, “well this doesn’t work,” or maybe it would have worked in black and white. So I think, much like what you're saying with the black and white, it can kind of be part of what you're doing without necessarily thinking about it.

K: Yeah, I think it becomes less and less of a conscious thought. You have this language that you use, and that's just your natural way of working. It’s not really something I think too much about anymore. With the color work, the summer project, it has definitely been a conscious thought. I’m trying to figure out how to look at that work objectively as color photos, and knowing when it works and when it doesn't. And that’s been a lesson with those photos, because I’ve never worked so extensively in color. Almost the whole time I've been photographing, it’s been black and white. So it's learning how to judge that work, and knowing when it works and when it doesn't.

S: Actually, speaking of your work and color – the phone work is really interesting. And I remember last year you were telling me how that came about. That you were assisting on a workshop with Gus Powell, and obviously you weren’t going to be able to develop your stuff during the weekend. Again, I don't know that I have a question about it other than… clearly you've kind of kept going with that stuff. How does it relate to your other work?

K: It’s something that I think more and more about. It’s become more of a thing in the last year, year-and-a-half. I think in some ways it's kind of like a sketchbook because it's very easy and accessible, in a way of seeing scenes photographically, quickly. I think I work differently with the phone. It’s much more intuitive, and for a long time the bar was much lower with the phone. Like, “that's interesting” and try to frame it nicely, and that was it… post to my account. I shoot exclusively in square with the phone, and I did that for a while and then I ended up getting a Rolleiflex. So it bleeds over in a lot of ways into the “real” photography. Although I think it’s become another outlet of that. So it influences in a lot of ways. And yeah, there was the Gus workshop I was assisting on, and I ended up doing an edit of phone photos from the weekend, and he actually had a really positive overall reaction to it. And it wasn’t work that I really thought much of prior to around that time. And then he was like, “maybe there's actually something here.” And that's part of where that idea of the interaction between man and nature came from – he was kind of picking up on that in that work. And it made me think, maybe you can make work with a phone. But even up to this point, it still has just been like a little outlet for me. It's still not something I take seriously, as I do the camera work.

S: No, but that's good. Because the reason you started it was not taking it seriously, right? So you almost don't want to…

K: You don’t want to taint it with that serious photography approach. But also, in a way, there’s still that thought and that attention when I’m taking those photos, trying to frame things a certain way. The things that I photograph, for me, only work with the phone a lot of the time. They’re things that most of the time, I wouldn’t photograph with the camera. There’s definitely been the issue where I photograph with both. And I’ll put the phone photo out into the world, and then I kick myself later because I see the camera photo…

S: And it’s better…

K: And I’m like, “shit!” But it’s of the same scene. And now it’s like, damn, the people that see that work, they’ve seen that, and then when they see the other photo… it’s not new. So I try to be conscious of not photographing the same scene, at least not in the same way. Maybe there’s a detail that I’ll photograph with the phone. And then the larger scene is in the camera photo.

S: When you first started… because that's what I'm trying to imagine, since I've barely done any stuff with the phone. But at the beginning, when you were walking around with your camera and your phone, what about a scene would make you go to the phone and not the camera?

K: I guess initially, the only way I can phrase it is that the bar was lower. It doesn't take as much for me to pull out my phone and be like, “That's interesting,” or look at the way the light’s hitting that. But it was a totally surface level attraction to something. It could still be about form and shape and content, but it was just a small detail that maybe either was about color – I think that became my color camera for a while – or just smaller details of things in that didn't resonate with me beyond a photo with the phone. And it’s still embarrassing that I shoot so obsessively with the phone. I’ll take fifty photos or more, maybe a hundred of the same exact photo. I'm trying to catch something in a certain way, or trying to frame something where it just hits the edge of the frame. It's kind of ridiculous, sometimes.

S: I was just going to say, you think you're approaching something on a surface level, but because you've honed your eye with photography in general, I don't think that that's actually true. I think you’re revealing that it's not actually as casual as even you realize, right?

K: Yeah, maybe it’s just the way that I see it and then I just put it out there without really much regard. I mean, most things that I post with those images are within 30 seconds or a minute after I took it. But there’s definitely a level of attention, like I said, and respect, I guess, for those images, and trying to make something worthwhile, or worth looking at. I don't want to be lazy with it. I want to make it interesting photographically. And sometimes that’s not the case. Sometimes there's not much thought to it, it's just an instinct. Here's this thing, or here’s a cloud, or light on the ground, you know what I mean? It’s just a totally different, more reactive, maybe more visceral approach sometimes. What sparks it is just different. I don’t know that I can put a finger on what that is. Some things just feel like a phone photo. Some things are for both differently, some things are strictly phone, some things are too good for the phone and they’re a camera photo. It’s not something that I’m conscious of, where that line is. But it’s interesting that it’s become more and more of a thing – that the phone has become more of a tool that I respect and go to a lot of the time.

Stephen Shore, from Transparencies (1974)

S: I’ve been thinking about that a lot, because more than COVID or something, I think in terms of what people will look back on in photography in 50 years, it’s going to be this question. Of always having a camera in your pocket on you, and the way that the phone sees. And yet, it’s not a new thing at all. I got this book that just came out of Steven Shore’s called Transparencies. It's basically his 35mm work that he was doing at the same time as the large format work in Uncommon Places.

K: I just ordered it too.

S: So in a way, your 35mm is like his 8x10, and your phone is like his Leica 50 years ago. It’s kind of the same problem – it sees differently, it feels casual, and yet there's something captured there that is valuable, independent of your “serious” work.

K: And with him as an example, that work definitely feels a lot to me like iPhone work of today for a lot of people, very reactionary. And now you see him, he’s working with an iPhone. Most of his work now is made with a phone, so maybe there is something to that. That was his iPhone of that time.

S: There’s also a parallel to that whole Szarkowski mid-century American thing where suddenly the amateur snapshot was embraced as having photographic value, and influenced serious photographers. And the exact same thing is happening, in a way, with phone photography. More of a quick feedback loop though, because back in the day, where would you see snapshots? You’d see them in your family albums, or you’d see them in a bin at a thrift store or something. But now we're just seeing them all the time, and it's this instant feedback.

K: In a live feed…

S: But it’s the same thing – it’s vernacular uses of photography influencing more… serious is not the right word. More deliberate forms of photography, let’s say.

K: Yeah, and the phone being respected more and more as a photographic tool as it’s become more prevalent. And it’s one of the most accessible for people, whether you have a camera or not, most people are seeing the world through the scope of their camera phone, through that view. So I guess it's the most widely accessible medium, just as small cameras, when they came around that time, mid-century, it was that same thing. The small 35mm camera made it accessible for more people, and kind of broadened that world. Maybe it's the same thing. I don't know. This is the most I thought about the phone in a while... the deepest I’ve gone.

S: Happy to oblige. Speaking of new books, anything else that’s been on your radar recently? Not necessarily a book, but what are you looking at right now? By the way, that Doug DuBois book [… all the days and nights] you posted about is crazy. That book just blew my mind.

K: Yeah, same. Actually speaking of that book, one of the things I’ve been thinking about – this might go off the rails again from your original question – but that work was one of the things that sparked the idea of doing personal family work with a larger camera. Because I think that’s all 6x9. And that's a camera that I've been having trouble incorporating into that type of work, that family documentary type of work that I do, but I’ve been trying to do more of. So seeing work like that, or Steinmetz’s approach with that camera, with people, that feels more responsive or quicker, or reactionary to a lot of scenes – that was something that kind of sparked that idea for me. I mean, other work, I’ve maybe been looking at too much Robert Adams. I look at a lot of his stuff. I try to limit that, so it doesn’t creep in too much. And Steinmetz. I just bought a handful of books, Susan Lipper’s Domesticated Land, which is one that had been on the list for a while. What else did I get? Jason Fulford’s Picture Summer On Kodak Film

S: I just got that too.

K: And that one was definitely just… color photos about summer. So, kind of inspiration for that whole project.

S: He's another one who uses the power of a small amount of words to animate or bring together photos.

Robert Adams, Colorado Springs, Colorado (1968)

K: Yeah, very much so. They give you that kind of loose, initial structure of what’s to come in the book. And it helps define that work, or gives you a guideline to follow. But it could just be a snippet or phrase. Those are the main ones that come to mind lately, but like I said, I try to be conscious of not looking at work that looks too much like my work. Speaking of somebody like Robert Adams, to me he’s a clear influence, sometimes too much. But I try to be conscious of not looking at a lot of his stuff that relates too much to my own. Not that I think I’m making work anywhere on his level, but when the subject matter is similar, and the format is similar, and that way of thinking – that stuff can bleed through too much. I try to step back from it.

S: That’s true, although I think at least for me, what I'm looking at goes through these intense phases, and so it's okay to me if something is kind of there for a month or two, and then after a little while – not that it goes away – but I think naturally something else comes up that has my eye at that moment.

K: Yeah, but do you find that if you go through one of those kind of phases with a certain photographer, or a certain style of work, that it kind of bleeds into your photos?

S: Sure. But I think it's the kind of thing where you can try to copy other people, and unless you happen to be really good at mimicking certain things – if you’ve put in the time and the practice and the work, and you have some idea of what it is that you yourself want to do – I think it still comes out as you. But I totally agree with you that there's a danger there, and it can get a little mimic-y.

K: Yeah. Those influences are always there, of course. But sometimes I feel there's a danger in oversaturating my mind with certain work for too long, if I’m working in that same realm.

S: I think also, there's a certain comfort – just like with music, too – to going back to the stuff that you know well, and you know always makes you feel good. There's that dopamine rush for me opening up an Eggleston book. But, on the other hand, taking the time to look at work that's a little away from what you typically do, or that’s a little more challenging. Not that Eggleston’s not challenging, but I mean work that’s not in your comfort zone in terms of what you always like to look at.

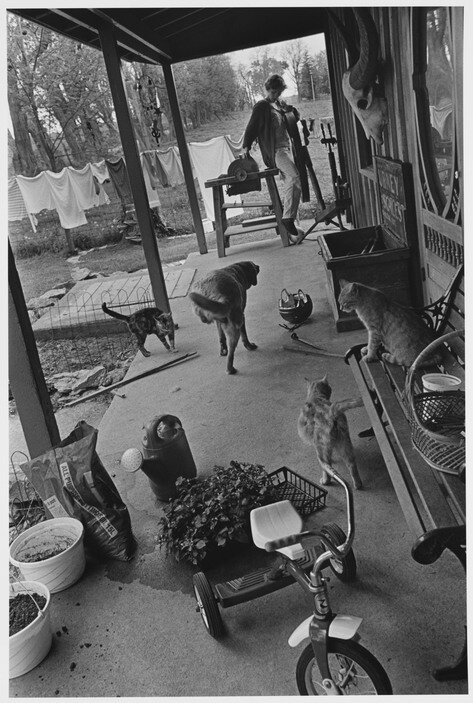

Larry Towell, from The World From My Front Porch

K: I think on the flipside is something that I’ve thought about more in the last couple weeks… I’ve gone back and forth between the landscape work and the family documentary type of work. And a lot of that is camera-based, because like I said, I'm having trouble with the medium format camera making that same style of work with the family, so I’ve been trying to incorporate it more. But I wanted to get back to that, so to jumpstart that again, I’ve been looking at work of people in that style that I respond to, like Larry Towell The World From My Front Porch type of stuff, that family documentary work. It’s very strong composition, strong layering, that type of thing. So, there's times where you want to get away from a certain type of work so it doesn't influence you too heavily, but it can sometimes also help get you back into a mindset or approach. I guess that can go either way.

S: So what else is on the horizon for you? We talked about the summer project. Are you thinking towards any other new project or zine, or just kind of photographing and going with it?

K: No, photo-wise, that's the only project. I’ve been shooting some more landscape-ish stuff that doesn't involve a human element lately, which has been different. I haven't developed any of the work, so I don't know if there's anything there. I have some loose ideas in mind about that, and where that could go, but that's a couple weeks in. So that's very fresh on my mind and I'm still working through that. I guess the only real conscious thing I’m working on, beyond the ongoing family stuff, is the summer project. It’s funny, with the summer stuff and how it relates to coronavirus… how that is going to affect that work. Is this summer’s work going to look like “summer with coronavirus”? There might not be the family vacation, or going to the amusement park or the water park. I’m sure there won’t be. So it’s like, will this summer’s work stand apart from last summer’s in a way that feels like summer with coronavirus? It’ll just be at home, or it’ll be just my family at my mom’s house hanging out in the yard. It won’t be going to the pool or things like that. So I’ve been curious what that will look like.

S: But the answer is, you gotta just make the work…

K: It is what it is.

S: And then later you’ll sort out if you want to go down that road.

K: Yeah. And you can choose to make it about that, or you can edit it in a way that’s not. You can shoot whatever, but you can edit it in a way that it all blends and you don’t even know. Because the work isn’t vacation, or traveling. It’s still at home, or at family’s house or in a park. So I think a lot of it won’t be affected, but I’m just curious to see how work in general is affected by it. Especially something like summertime. What is summer without those types of things? That’ll be interesting to see.

Copyright © Sebastian Siadecki, 2020.